If you are a programmer who want to change the world, consider biology

This post is an attempt at convincing you that if you are:

- Good at programming

- Want to change the world

Then you should consider learning biology. To be more specific, you should consider applying everything you’ve learnt and will learn into biology-leaning applications. The title of this article could as well be “Why you, a biologist, should learn programming.” However, if you are a biologist, chances are you already learned some programming skills.

Because you can have immediate impact

Your personal impact within a field is potentially dependent on two components:

- How many problems your skillset can solve exist within that field?

- How many individuals with your skillset work in that field?

For someone who knows programming in biology, the answers to those two questions are respectively a lot and too little. This means that if you are planning to use your skillset in programming toward biology, there is a good chance your contribution might make immediate impact.

The hammers and the nails

Credit: James King-Holmes/Science Photo Library

Credit: James King-Holmes/Science Photo Library

You probably know DNA is the reason why you look like your parents. DNA is a large molecule that contains two backbones and two linked “sequences.” The sequences are composed of four types of bases/letters G, T, C, and A. It was the ordering of these four bases that code for everything that makes you, from the basics like how your heart works or how your thumbs are smaller than your fingers, to the uniques like your eye color or your allergies. Extracting the sequence of DNA in human has been the goal of biologists for a very long time. The first multinational project to sequence the entire human genome started in 1990. But sequencing DNA is not the same as reading binary lines on a computer line. DNA is extremely small and extremly compact: the human genome has 3 billion base pairs in total, squeezed into a space only 6 out of 1000 of a milimeter. No microscope was capable of making out the shape of the base pair, let alone reading what base it is.

Fortunately, sequencing machines back then can read the base pair of segments several thousands letters long through chemical methods. An approach was devised: divide the human genome into small segments, use the sequencing machines to produce results, then combine these results together. The implementations are nowhere as simple as the idea. Various algorithms were brought in from mathematics and computer science to find the best ways to reconstruct sequences. On an organizational scale, a larger problem emerged: each research lab was sequencing DNA in a different manner, producing results that are extremely hard to combine. Imagine working on a puzzle with billion of pieces with thousands of other people, and imagine the difficulty of keeping track of where the puzzles has been finished. By the mid-1990s, it was entirely unsure if progresses were going well given the state of mismatch between different labs across the continents.

Then came a rescue from the programming field. Less than a decade ago, a programmer for NASA created a new programming language called Perl to make text processing easier. As it happens, genome sequencing uses a lot of text. Not just the DNA letters themselves, but also annotations, comments, and bibilographies. The language quickly catched onto the genome sequencing project as a way to help research labs produce programs that are easily sharable. Ease of learning and writing helps a lot, too. Perl stays as a programming language of choice for many bioinformatics researchers, thanks in no part to its powerful text processing abilities1.

This brings me to the point I want to make: The world of computer science and programming is rich with advanced tools. The world of biology, on the other hand, isrich with problems that advanced tools can solve. If you, a programmer, want to contribute to biology, you can see yourself creating solutions that speed up current research much, much more. You can find existing computational methods and adapt them to biology applications, or you can help develop something as simple as new software to faciliate collaborations between scientists. Rest assure, building these systems might sound simple in your field, but they are far from obvious in research facilities.

Double Threats

Credit: MIT News

Credit: MIT News

[..] if you want something extraordinary, you have two paths: 1) Become the best at one specific thing. 2) Become very good (top 25%) at two or more things.

- Scott Adams

There are many people who are good at programming. There are also many people who are good at biology. But it is rare to find someone knowledgable in both. Let’s quickly look at how many people who work in programming-based occupations to get a sense of number2:

| Occupation | Number of jobs |

|---|---|

| Computer and Information Systems Managers | 482,000 |

| Hardware Engineers | 66,200 |

| Network Architects | 165,200 |

| Computer Programmers | 185,700 |

| Systems Analysts | 607,800 |

| Database Administrators | 168,000 |

| Information Security Analysts | 141,200 |

| Computer Systems Administrators | 350,300 |

| Software Developers | 1,847,900 |

| Web Developers | 199,400 |

| Computer Research Scientists | 33,000 |

| Total | 4,246,700 |

Now, let’s look at how many people work in biology or health-related occupations3:

| Occupation | Number of jobs |

|---|---|

| Biochemists and biophysicists | 34,800 |

| Biological Technicians | 87,600 |

| Laboratory Technologists | 335,500 |

| Medical Scientists | 133,900 |

| Microbiologists | 21,400 |

| Physicians | 727,000 |

| Pharmacists | 322,200 |

| Total | 1,662,400 |

That is almost 2.5 times less than the amount of people work in programming jobs already. Excluding physicians and pharmacists, the number drop down to 613,200, or 7 times less than the amount of people who work in programming. Finally, how many people can we estimate to be good in both fields? The only interdisciplinary field which I found that requires one to be proficient in both seems to be biomedical engineering, which has the following number:

| Occupation | Number of jobs |

|---|---|

| Bioengineers | 19,300 |

I hope I convey my points. This is not a detailed estimate and it ignores many things, but it conveys that there are far less people who work in biology than people who program, and there are far, far less people who can program well work in biology. Bringing your skills to biology means that you have a chance to become a so-called “double threat” per Scott Adams. This is not just about your chances for good employments–it is also about your chance to actually make a difference to the world. Given the large number of unsolved problems in biology, you have the potential to contribute to something really important and world changing. Could it be contributing to an open-source model of cancer? Or could it be writing a Python library to help CRISPR research? But what if you are not highly motivated by purpose, but rather financial? Rest assure that bringing your skills into biology might not be a bad financial play, because…

Bio is the new tech

Credit: David Parry / Reuters

Credit: David Parry / Reuters

Jobs that require programming skills are amongst the highest-paying jobs. Simply put, if you live in the United States and dedicate yourself toward becoming a software engineer, you can get a job that pays you more than $100,000 in annual salary. And if you manage to get yourself into a big public tech company (The most famous ones are called Big Five, which include Facebook/Meta, Google/Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft), your stock bonus can push your salary up beyond $200,000 right out of college. If you have a solid background in programming, why should you dedicate your skills toward less profitable applications in biology?

There are many parallels between the current state of biology, and the state of computers at the beginning of the 1970s. Remember mainframes? They were gigantic computers that take up a section of a room. Take a look at this to see how spreadsheet were done back in the day. Back in those time, computers were expensive, and their main customers were companies and research facilities. Then, a small and inexpensive computer called the Altair 8800 was released. It was the most influential personal computer of all time; its existence inspired Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak to release their own peronsal computers called the Apple I. It also launched the careers of Bill Gates and Paul Allen, who made intepreter for the Altair 8800. The rest is history. Personal computing didn’t just launch the careers of Apple and Microsoft, it launched the careers of millions of others and the development of the internet as well.

If we look at the state of biology research today, we found that there is a similar transformation underway. Biology research has mostly been done in research labs with million-dollar fundings and teams of PhD. But now, a series of innovations in basic research might upend everything:

-

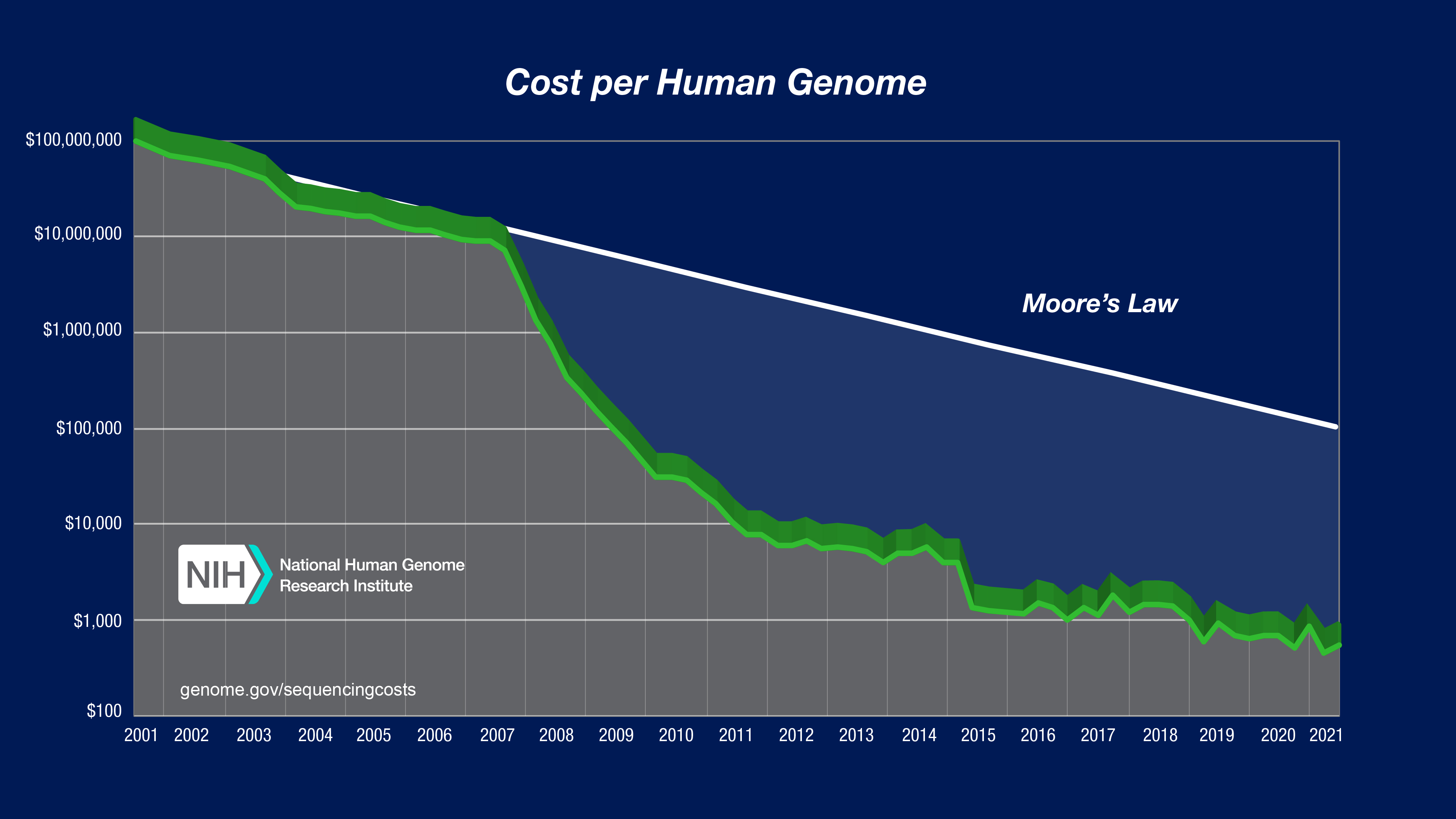

Remember the DNA sequencing story earlier? The entire human genome project was finished in 2003, took 13 years to complete, and cost $3 billion. The cost of sequencing genome dropped dramatically since then. You might be familiar with Moore’s law, which predicted that integrated circuits will continue to be denser. Geneticists are using a similar analogy toward genome sequencing, and predicted that the cost of genome sequencing will become exponentially lower over time. It was the lowering costs that led to the creation of many gene sequencing companies such as 23andMe or Ancestry.com.

-

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing was a method of modifying the DNA with much higher accuracy and lower cost than previous methods. How low-cost are we talking about? Low enough that you can mail-order it and do your own CRISPR experiments at home. In fact, similar to the HomeBrew club of computer hardware tinkerers in the 1970s, there is a subculture of biohackers who are willing to perform biomedical experiments in their homes, even on themselves.

Credit: National Institute of Health

Credit: National Institute of Health

Any technological revolution is preempted by decades of basic science. For biology, while it may seems that basic science research are still underway, you may not want to miss it in the next decade when the biotech revolution gets into full gear. Leaders in software technology surely saw the trends as well: Fundings for synthetic biology – developing new biological organisms – burgeoned from $10 billion 10 years ago, to almost $50 billion in 2018. Here is just a quick list of some companies that receive fundings from the like of Bill Gates, Jerry Yang, and Eric Schmidt:

- Bolt Threads, which engineer microbes to produce synthetic silks

- Upside Foods, which grow real meats from cell cultures

- Editas Medicine, which uses CRIPSR-Cas9 editing therapy to treat rare genetic diseases

- Lygos, which engineer microbes to convert sugar into industrial products

What should I do?

I hope that this essay was enough to convince you about the merits of using your skills in programming to apply toward biology. But how should you start? Not everyone who works in biology and biotech started the same, but here are some general ideas you can consider:

-

Learn. I recommend you start with A Computer Scientist’s Guide to Cell Biology. It explains biochemical processes in a simple and approachable way. Learn about DNA, RNA, and proteins. Familiarized yourself with evolution and natural selection. Then, if you want to specialize, learn about topics that interests you such as the immune system or behavioral biology. Biology is a large field. Take your time.

-

Experiment. Ask to work for a biomedical research lab. If it was good enough for Eric Lander or Richard Feynman, it certainly was good for you as a place to start. If you really want to get yourself a leg up, consider a postgraduate degree in biology-related fields as well.

-

Apply. If you are already working in a programming career, try to look around for places you can apply to. You can look at bioinformatics, biotech, or genetics companies.

-

Educate. Write blogs about what you have learned. Tell your friends and families about how biology works. Make videos about it. Make video games about it. There is a crisis in the United States when it comes to medicinal and healthcare education right now. If you can help with education, you are already changing the world.

-

Contribute. There are many community-driven, open-source projects in biology that you can participate right now without the need for a laboratory. Contribute to a bioinformatics library or a free artificial pancreas. If you get acess to a research laboratory, why not consider developing an affordable insulin alternative?

Conclusion: The charms of biology

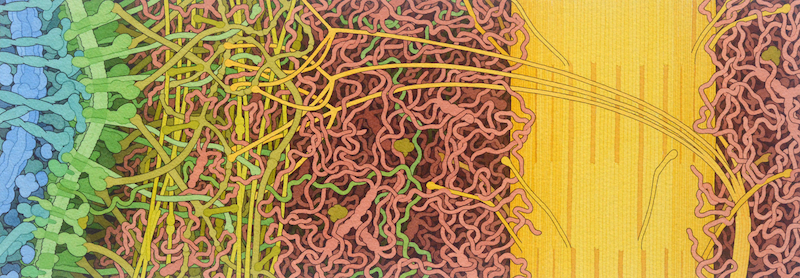

The extracellular matrix. Art by David Goodsell

The extracellular matrix. Art by David Goodsell

[…]So right away I found out something about biology: it was very easy to find a question that was very interesting, and that nobody knew the answer to. In physics you had to go a little deeper before you could find an interesting question that people didn’t know.

- Richard Feynman

The first essay that truly convinced me about the beauty of biology was James Somers’ I should have loved biology. It shows me that biology is the study of extremly complicated and mysterious mechanism that happen all around us. Within the mysteries also lie the charms. You may need to learn extra backgrounds to understand the importance of an unifying theory between general relativity and gravity, or the roadblocks toward feasible quantum computing, but studying aging and you will find more than 300 different theories on how and why the most inevitable biological pocess even occurs4. As a programmer, you likely learned thigs from first principle: a simple model or mathematical equation, then scaling up to adapt toward your needs. In biology, anything you encounter is often extremly complex, that any first-principle models would not be sufficient enough.

The charms of biology comes from the fact that studying biology is akin to study advanced technology from a different civilization. The eukaryotic cell is the most complex nano-machine in the known universe. We still do not understand the true reason why we dream, nor what is conciousness and free will. The open-endedness of evolution is something beyond the grasps of current evolutionary algorithms. There are many reasons why you, a programmer, should consider biology. I have laid out my arguments that you can make an far greater impact on the world if you use your skills in a disciplinary fashion, that you are on a cusp of a biotechnology revolution. But in case these haven’t convinced you enough, I will give you the reason why I considered biology: because it is extremely fascinating.

-

Source: Bureau of Labor ↩

-

Source: Bureau of Labor ↩

-

Source Viña et al. ↩